The Sumerian Standard of Ur Created Between 2600 and 2400 Bce Is an Example of What Art Form?

| The Standard of Ur | |

|---|---|

"State of war" panel | |

| Material | shell, limestone, lapis lazuli, bitumen |

| Writing | cuneiform |

| Created | 2600 BC |

| Discovered | Royal Cemetery |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Identification | 121201 Reg number:1928,1010.3 |

The Standard of Ur is a Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the British Museum. Information technology comprises a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (eight.l in) broad by 49.53 centimetres (xix.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of vanquish, blood-red limestone and lapis lazuli. It comes from the ancient city of Ur (located in modern-day Iraq west of Nasiriyah). It dates to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic catamenia and is around 4,600 years old. The standard was probably constructed in the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of state of war and peace represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although interpreted every bit a standard by its discoverer, its original purpose remains enigmatic. Information technology was found in a majestic tomb in Ur in the 1920s next to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed human who may have been its bearer.

History [edit]

The Standard of Ur, in the British Museum.

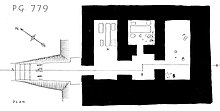

The artifact was found in one of the largest majestic tombs in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, tomb PG 779, associated with Ur-Pabilsag, a male monarch who died around 2550 BC.[1] Sir Leonard Woolley's excavations in Mesopotamia in 1927–28 uncovered the artifact in the corner of a chamber, lying shut to the shoulder of a man who may take held it on a pole.[2] For this reason, Woolley interpreted it as a standard, giving the object its popular name, although subsequent investigation has failed to confirm this supposition.[3] The discovery was quite unexpected, as the tomb in which it occurred had been thoroughly plundered by robbers in ancient times. As one corner of the final chamber was being cleared, a workman spotted a slice of shell inlay. Woolley later recalled that "the next minute the foreman's paw, advisedly brushing abroad the earth, laid bare the corner of a mosaic in lapis lazuli and beat."[4]

Program of grave PG 779, idea to belong to Ur-Pabilsag. The Standard of Ur was located in "S"

The Standard of Ur survived in only a bitty condition. The ravages of time over more than four thousand years acquired the decay of the wooden frame and bitumen gum which had cemented the mosaics in identify. The soil'southward weight crushed the object, fragmenting information technology and breaking its terminate panels.[2] This made excavating the Standard a challenging task. Woolley's excavators were instructed to look for hollows in the ground created by decayed objects and to fill them with plaster or wax to record the shape of the objects that had once filled them, rather like the famous plaster casts of the victims of Pompeii.[5] When the remains of the Standard were discovered past the excavators, they constitute that the mosaic pieces had kept their form in the soil, while their wooden frame had disintegrated. They carefully uncovered modest sections measuring most three foursquare centimetres (0.47 sq in) and covered them with wax, enabling the mosaics to be lifted while maintaining their original designs.[6]

Clarification [edit]

The present form of the antiquity is a reconstruction, presenting a all-time gauge of its original appearance.[2] It has been interpreted as a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (viii.50 in) broad by 49.53 centimetres (xix.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of beat, ruddy limestone and lapis lazuli. The box has an irregular shape with terminate pieces in the shape of truncated triangles, making it wider at the bottom than at the tiptop, along the lines of a Toblerone bar.[3]

Inlaid mosaic panels cover each long side of the Standard. Each presents a series of scenes displayed in iii registers, upper, middle and bottom. The two mosaics accept been dubbed "State of war" and "Peace" for their discipline matter, respectively a representation of a military campaign and scenes from a feast. The panels at each finish originally showed fantastical animals but they suffered significant damage while cached, though they have since been restored. Both sides use hierarchical proportion in the depiction of the forms of the art, with the most important individuals appearing larger than less important ones.

Mosaic scenes [edit]

"Peace", detail showing lyrist and maybe a singer

"State of war" is one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian regular army, engaged in what is believed to exist a border skirmish and its aftermath. The "War" console shows the king in the middle of the height register, standing taller than any other effigy, with his head projecting out of the frame to emphasize his supreme status – a device as well used on the other panel. He stands in front of his bodyguard and a four-wheeled wagon,[note 1] fatigued by a team of some sort of equids (perchance onagers or domestic asses;[7] [8] horses were only introduced in the 2d millennium BC after being imported from Cardinal Asia[9]). He faces a row of prisoners, all of whom are portrayed equally naked, bound and injured with large, bleeding gashes on their chests and thighs – a device indicating defeat and debasement.[iii] In the middle register, eight virtually identically depicted soldiers give way to a battle scene, followed by a depiction of enemies being captured and led away. The soldiers are shown wearing leather cloaks and helmets; actual examples of the sort of helmet depicted in the mosaic were constitute in the aforementioned tomb.[v] The nudity of the captive and expressionless enemies was probably not meant to describe literally how they appeared in real life, only was more likely to take been symbolic and associated with a Mesopotamian belief that linked death with nakedness.[ten]

The lower annals shows 4 wagons,[note one] each carrying a driver and a warrior (conveying either a spear or an axe) and drawn by a team of four equids. The wagons are depicted in considerable detail; each has solid wheels (spoked wheels were not invented until about 1800 BC) and carries spare spears in a container at the front. The organization of the equids' reins is also shown in detail, illustrating how the Sumerians harnessed them without using bits, which were only introduced a millennium later.[5] The wagon scene evolves from left to right in a style that emphasizes motion and action through changes in the depiction of the animals' gait. The first wagon team is shown walking, the second cantering, the third galloping and the fourth rearing. Trampled enemies are shown lying under the hooves of the latter 3 groups, symbolizing the potency of a carriage attack.[iii]

"Peace" portrays a feast scene. The king once more appears in the upper register, sitting on a carved stool on the left-manus side. He is faced by half dozen other seated participants, each property a cup raised in his right paw. They are attended by various other figures including a long-haired private, perchance a vocaliser, who accompanies a lyrist. In the centre annals, baldheaded-headed figures wearing skirts with fringes parade animals, fish and other goods, perhaps bringing them to the feast. The lesser annals shows a series of figures dressed and coiffed in a unlike way from those higher up, carrying produce in shoulder numberless or backpacks, or leading equids by ropes attached to olfactory organ rings.[3]

Interpretations [edit]

The original function of the Standard of Ur is non conclusively understood. Woolley's suggestion that information technology represented a standard is at present thought unlikely. It has also been speculated that it was the soundbox of a musical instrument.[2] Paola Villani suggests that it was used as a breast to store funds for warfare or ceremonious and religious works.[11] It is, however, impossible to say for sure, as at that place is no inscription on the artifact to provide any background context.

Although the side mosaics are commonly referred to equally the "war side" and "peace side", they may in fact be a single narrative – a boxing followed by a victory celebration. This would be a visual parallel with the literary device of merism, used past the Sumerians, in which the totality of a situation was described through the pairing of opposite concepts.[12] [xiii] A Sumerian ruler was considered to have a dual role every bit a lugal (literally "big man" or war leader) and an en or borough/religious leader, responsible for mediating with the gods and maintaining the fecundity of the land. The Standard of Ur may have been intended to depict these two complementary concepts of Sumerian kingship.[3]

| External media | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sound | |

| | |

| Video | |

| |

The scenes depicted in the mosaics were reflected in the tombs where the "Standard" was plant. The skeletons of attendants and musicians were plant accompanying the remains of the kings, every bit was equipment used in both the "War" and "Peace" scenes of the mosaics. Unlike aboriginal Egyptian tombs, the dead were not buried with provisions of food and serving equipment; instead, they were institute with the remains of meals, such equally empty food vessels and animal bones. They may have participated in one terminal ritual banquet, the remains of which were cached aslope them, earlier being put to decease (maybe by poisoning) to back-trail their master in the afterlife.[15]

Run across also [edit]

- Lyres of Ur

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Anthony (2006, p. 5): "Wagons have four wheels, carts have 2, and chariots accept two spoked wheels, so that the vehicles on the Ur Standard are wagons, not chariots, as they are often called."

References [edit]

- ^ Hamblin, William James. Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history, p. 49. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- ^ a b c d The Standard of Ur, British Museum. Accessed 2010-12-05.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Zettler, Richard L.; Horne, Lee; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly. Treasures from the royal tombs of Ur, pp. 45-47. UPenn Museum of Archeology, 1998. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3

- ^ Woolley, Leonard (1965). Excavations at Ur: a record of twelve years' work. Crowell. p. 86.

- ^ a b c Collon, Dominique. Ancient Near Eastern Art, p. 65. University of California Printing, 1995. ISBN 978-0-520-20307-5

- ^ Chadwick, Robert (1996). First Civilizations: Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. Editions Gnaw Fleury. ISBN9780969847113.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1992). Horse Power: A History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies. U.Southward.: Harvard Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-674-40646-9.

- ^ Anthony 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Gates, Charles (2003). Ancient Cities: The Archeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Arab republic of egypt, Hellenic republic and Rome. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN9780415121828.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (2001). Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN9780415218306.

- ^ Settemila anni di strade. Milano: Edi-Cem. 2010.

- ^ Harrison, R.K. "Genesis", p. 441 in Bromiley, Geoffrey West. (ed.), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0

- ^ Kleiner, Fred Due south. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, p. 24. Cengage Learning, 2009. ISBN 978-0-495-57360-9

- ^ "The Standard of Ur". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, Andrew C. Death rituals, ideology, and the development of early Mesopotamian kingship: toward a new understanding of Iraq'south purple cemetery of Ur, p. 92. BRILL, 2005. ISBN 978-90-04-14635-eight

Sources [edit]

- Anthony, David Due west. (2006), "The Prehistory of Scythian Cavalry: The Evolution of Fighting on Horseback", in Aruz, Joan; Farkas, Ann; Valtz Fino, Elisabetta (eds.), The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Perspectives on the Steppe Nomads of the Ancient World, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, Northward.Y.)

External links [edit]

- Podcast of The Standard of Ur BBC Radio programme (mp3)

- What is the Standard of Ur?

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_of_Ur